Expected Ratio?

In film, aspect ratio is defined as the proportional relationship between an image’s width and height, expressed by placing the two variables side by side and separating them with a colon. Depending on your viewing method, the aspect ratio could drastically change. In the earlier ages of film and TV, dimensions of images on select film stock typically determined the aspect ratio for all audiovisual entertainment. Until the 1980’s when TV and film were found in different settings and therefore were depicted in different aspect ratios. TV was often consumed at home on box television sets, which portrayed a fairly square aspect ratio of 1.33:1 or 4:3, hence the name box sets. Opposing this, rectangular widescreen movies were shown in theatres with a ratio of 2.39:1, also standard in the early 1980s. However, once entertainment progressed past the medium of film and started shooting digitally, the purpose of aspect ratio changed in the audiovisual industry. What once felt like an adherence that filmmakers were forced to work around is now used stylistically and is sometimes even changed mid-film.

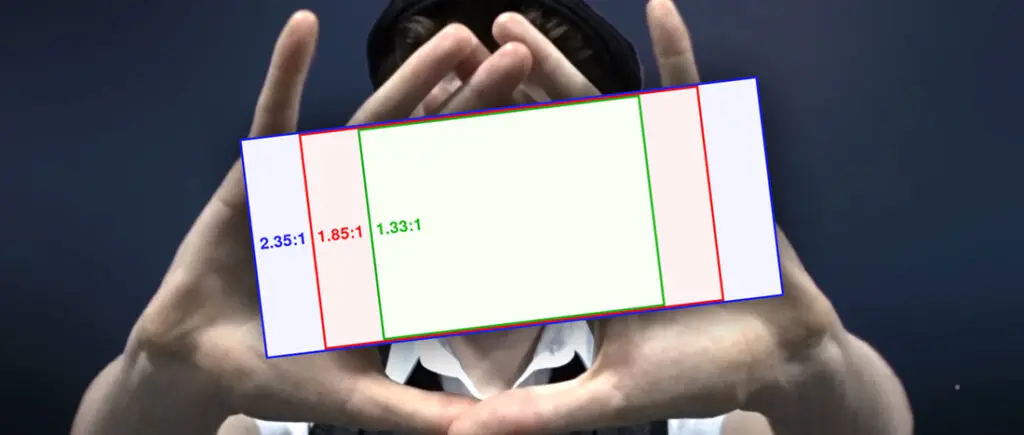

In the early 1900’s the first film stock consisted of .95 inch by .735 inch images that allowed movies to be projected at an aspect ratio of 4:3. The addition of synchronized sound in the 1920’s altered the composition of film stocks and therefore shrunk the size of the images on them. This consequently brought the standard aspect ratio down to 1.37:1. This solidified 1.37:1 as the Academy Ratio, the only aspect ratio to be recognised by the Academy of Motion Pictures. This remained the most popular width to height ratio for movies until 1952, when Cinerama debuted a 3 projector system that introduced the widescreen format to audiences, which is standard in theatres today. Far wider than what modern audiences are used to today, the ratio for Cinerama films was a staggering 2.59:1. However, this method was soon outperformed by 1 projector systems, which were favoured by theatres due to their simplicity and cost efficiency. The race for the ideal uni-projector widescreen format was picking up rapidly. Movie, production and distribution companies created their own systems in the hope to produce the clearest image and most efficient process among the competition. As the 2000s approached, the standard aspect ratio for movies grew closer and closer to what we see in theatres today. Ultimately, 20th Century Fox’s Cinemascope, with an aspect ratio of 2.35:1, was the most popular ratio used among filmmakers by the early 2000s. At this time, film screen ratios normally went no wider than 2.35:1, and television’s rarely varied from 4:3. As a means to bridge the gap, the mean of these two very values was used to determine the aspect ratio that we most commonly see a quarter-century later.

Currently, 16:9 is the standard aspect ratio for most audiovisual content currently excluding film theatres whose screens still accommodate the 2.35:1 ratio largely to maintain the grandeur experience of cinema. The prominence of 16:9 in media determined the screen dimensions of many modern-day technologies: widescreen televisions, touchscreen phones, and most Youtube videos. However, movies still premiered at a slightly wider ratio of 2.35:1. Despite this difference, television channels still frequently broadcasted movies and films that they had the rights to. The quid pro quo of profiting from cinema via the television medium ultimately circles back to aspect ratio. Letter boxing is a technique used to fit media of one aspect ratio on a screen that may have different dimensions. It is most often used to fit wider media into less wide aspect ratios, resulting in negative space on the top and bottom sides of the screen. As movies were often shown on TV, the infamous surrounding bars gained their own rhetoric among TV and moviegoers alike. Sooner rather than later, letterboxing became a cognitive symbol that represented the true cinematic experience to audiences. An early example of this can be seen in ’90s and early ’00s video games, such as “Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II” and “Tomb Raider.” Cutscenes in these games feature letterboxing, which signals plot development and uses a focal point to focus the player on story-building dialogue. Recently, this practice has lost traction due to the prominence of wide-screen TVs and 9:16 aspect ratios across most video game platforms.

In this way, letterboxing has evolved from a conventional editing tactic to a cinematic stimulus for modern audiences. Harper Cossar explains in her article The Shape of New Media: Screen Space, Aspect Ratios and Digitextuality that letterboxing occurs when “something extraordinary is taking place, and viewers should observe.” Similar to how 2.35:1 ratios have adopted a specific meaning to their audiences, other ratios have this effect as well. “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire” demonstrates this superbly. The beginning of the film is shown in a movie’s standard 2.35:1 ratio. This chunk of the film includes the exposition and rising action leading up to the games. As Katniss, our main character, transitions from training for the Hunger Games into the actual games, the screen transitions with her. Evolving from a 2.35:1 ratio to 1.78:1 for a taller, more immersive effect, which is standard for IMAX features. The letterboxed portion of the movie, once again, proves to be informative, plot-building, and explicative, while the transition away form the signature black bars signifies the movies breach into the climax of the film. This contributed to the heightened experience of the climax and paired perfectly with “Catching Fire’s” drastic change in setting and tempo in this scene.

4:3 aspect ratios are still utilised in modern cinema as well. While it is rarer than 2.35:1 or 1.78:1 ratios, the ratio that started it all still holds meaning of its own. Mostly seen as an artistic choice now, 4:3 has a plethora of uses for filmmakers. Obviously, being one of the first ratios of the audiovisual world, naturally 4:3 in modern media is often used to reference early media, signify flashbacks, or induce nostalgia. Films like the Grand Budapest Hotel switch to this ratio when the plots events are taking place in the time period synonymous to 4:3. Another example of this is seen in the film mid 90’s. While the film’s events aren’t during 4:3’s prominent era, it is still utilized this ratio to elicit a sense of nostalgia and does a great job of doing so. Considering the film takes place in the ’90s, but was made nearly two decades after 2000, choosing 4:3 was a strategic choice in an attempt to give the film a more dated look. This, in turn, complemented the aesthetic of the film as a whole by enhancing its vintage feel. Other films utilize the square-like dimensions of 4:3 stylistically. The reduction of width that most moviegoers are used to creates a claustrophobic feel that is great for the eeriness of a horror movie. With that being said, 4:3 is no exception to the rhetoric behind the use of aspect ratios in modern audiovisual media.

The dimensions of movies, TV, and online video always begin with a set or standard ratio, but as time has progressed, this practice could not be any more different. Now that aspect ratio have evolved into the cinematic device that it is today, there truly is no expected ratio in the film or tv community. Rather, through techniques such as letterboxing and cropping, we are able to distribute media of all sizes onto any platform, giving filmmakers more freedom than ever before. While some ratios still prove to be more popular than others, it is ultimately up to the creator to decide which ratio best suits the intention of their work.

It’s really intriguing to read about the history of aspect ratio. I never realized that the aspect ratio of TV was initially shaped by the physical dimensions of the sets. Definitely gives more context to why certain films feel ‘wide’ in theaters!